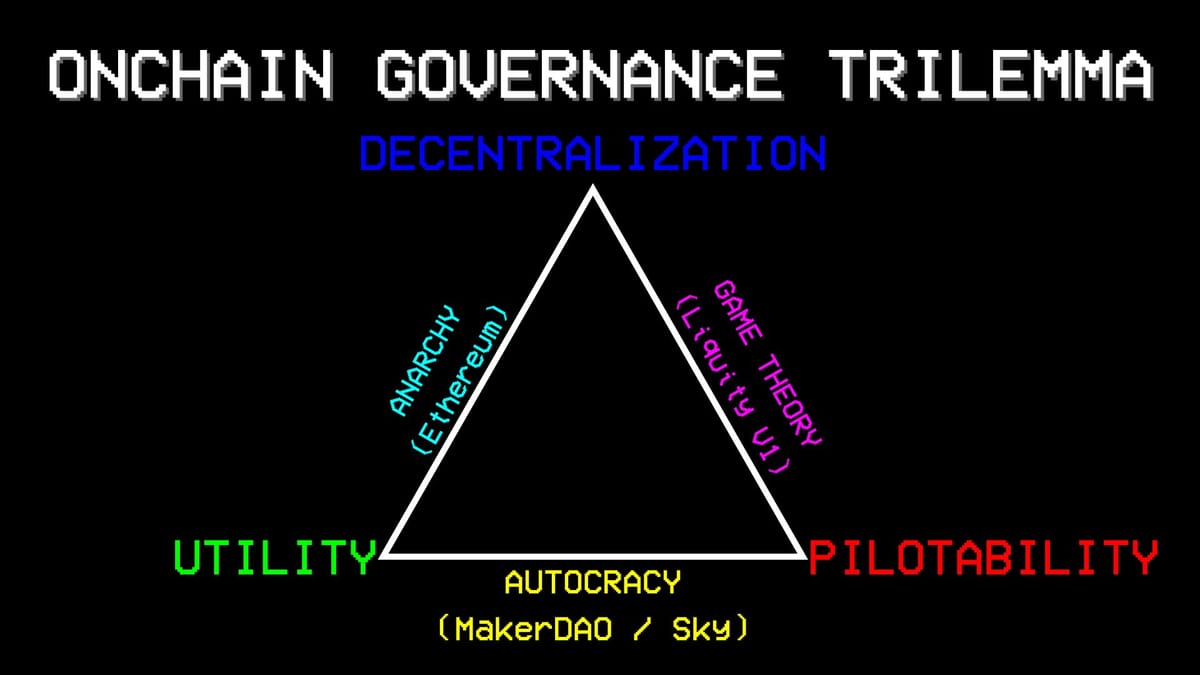

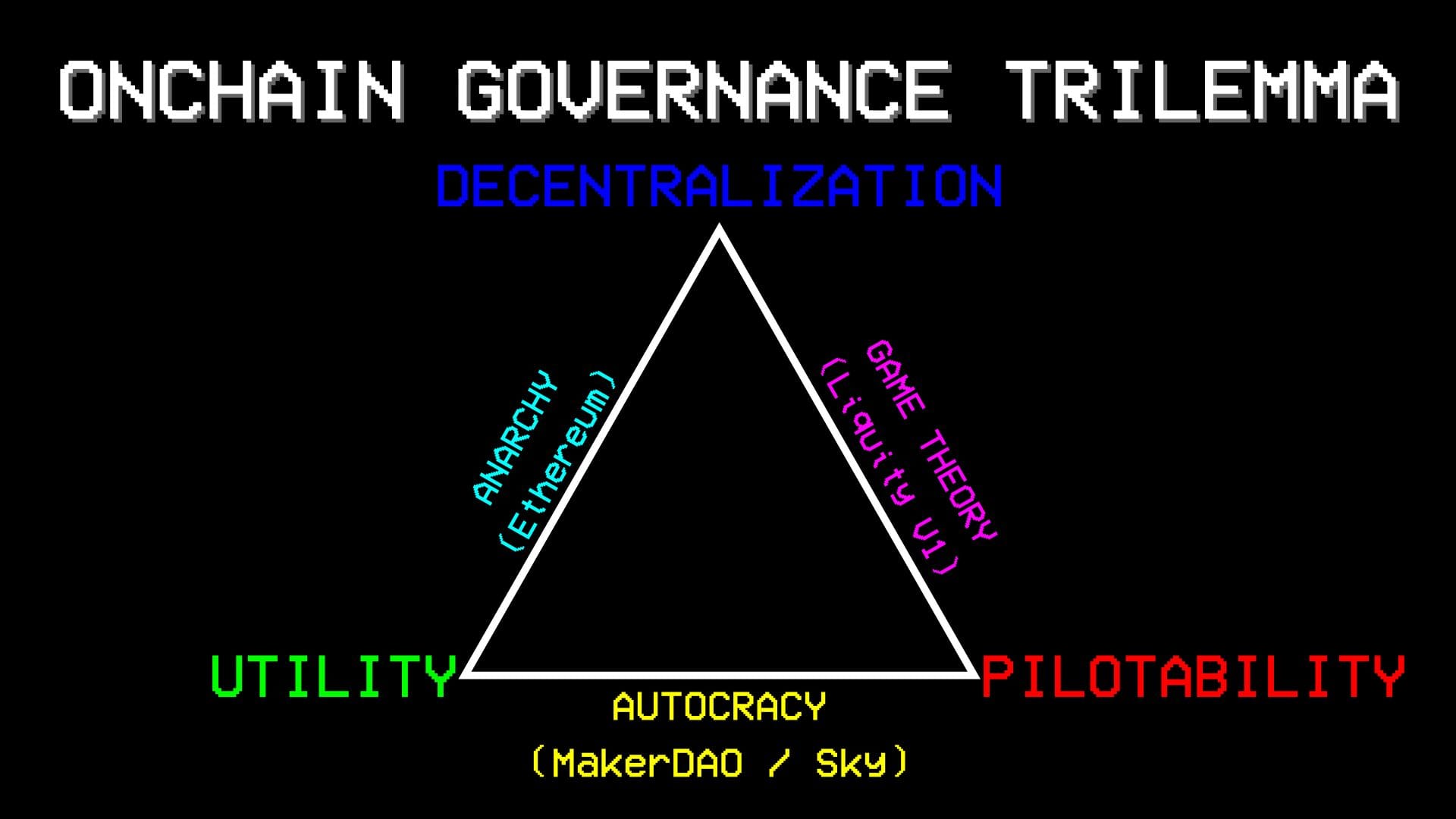

The onchain governance trilemma

Onchain governance is cool and all, until we realize blockchains can't solve all the problems

Most of the time, applications developed on blockchain are created and managed by core teams in a company. That said, some projects are decentralizing project governance, i.e. future decision-making of the whole project.

Onchain governance is seen as a real evolution in how we govern, with total transparency and the possibility of coordinating independent entities.

However, the more we dig into onchain governance, the more we realize we face limitations.

We're used to talking about the “blockchain trilemma” (decentralization, scalability, security), in which we're forced to sacrifice one feature to benefit the other two.

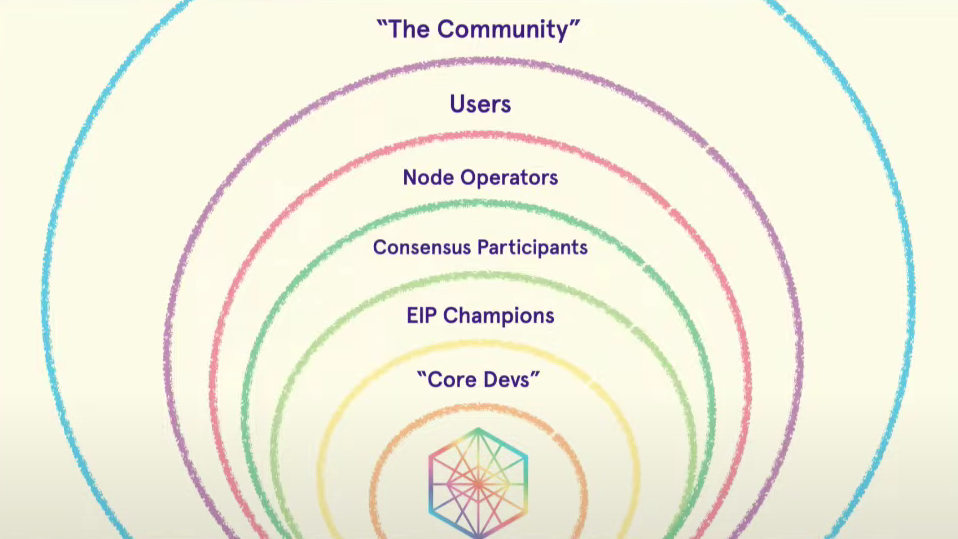

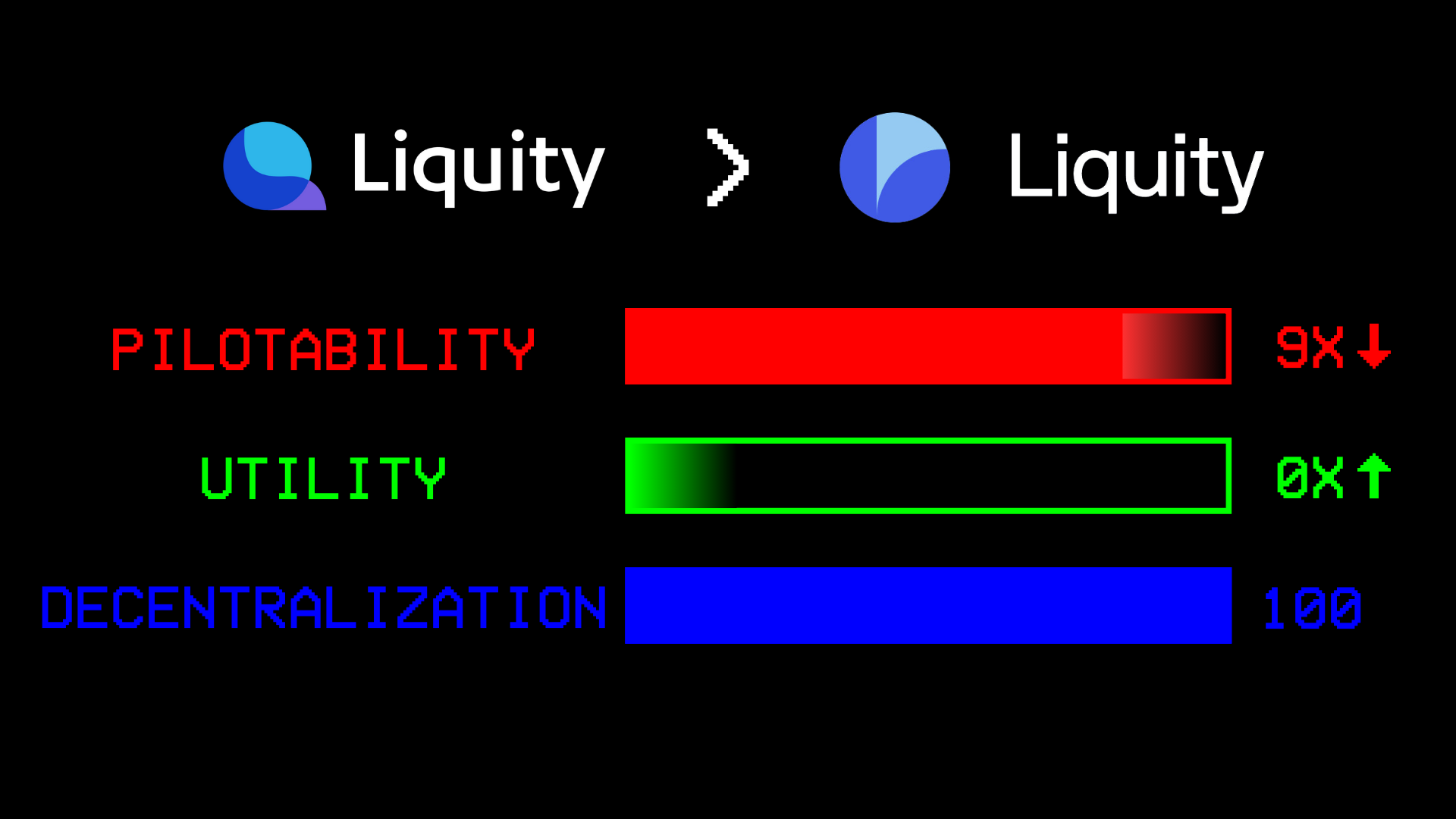

From a certain point of view, onchain governance also faces a trilemma:

- Utility: the influence of a token on a project

- Decentralization: independence of entities/absence of leadership

- Pilotability: the ability to make decisions quickly

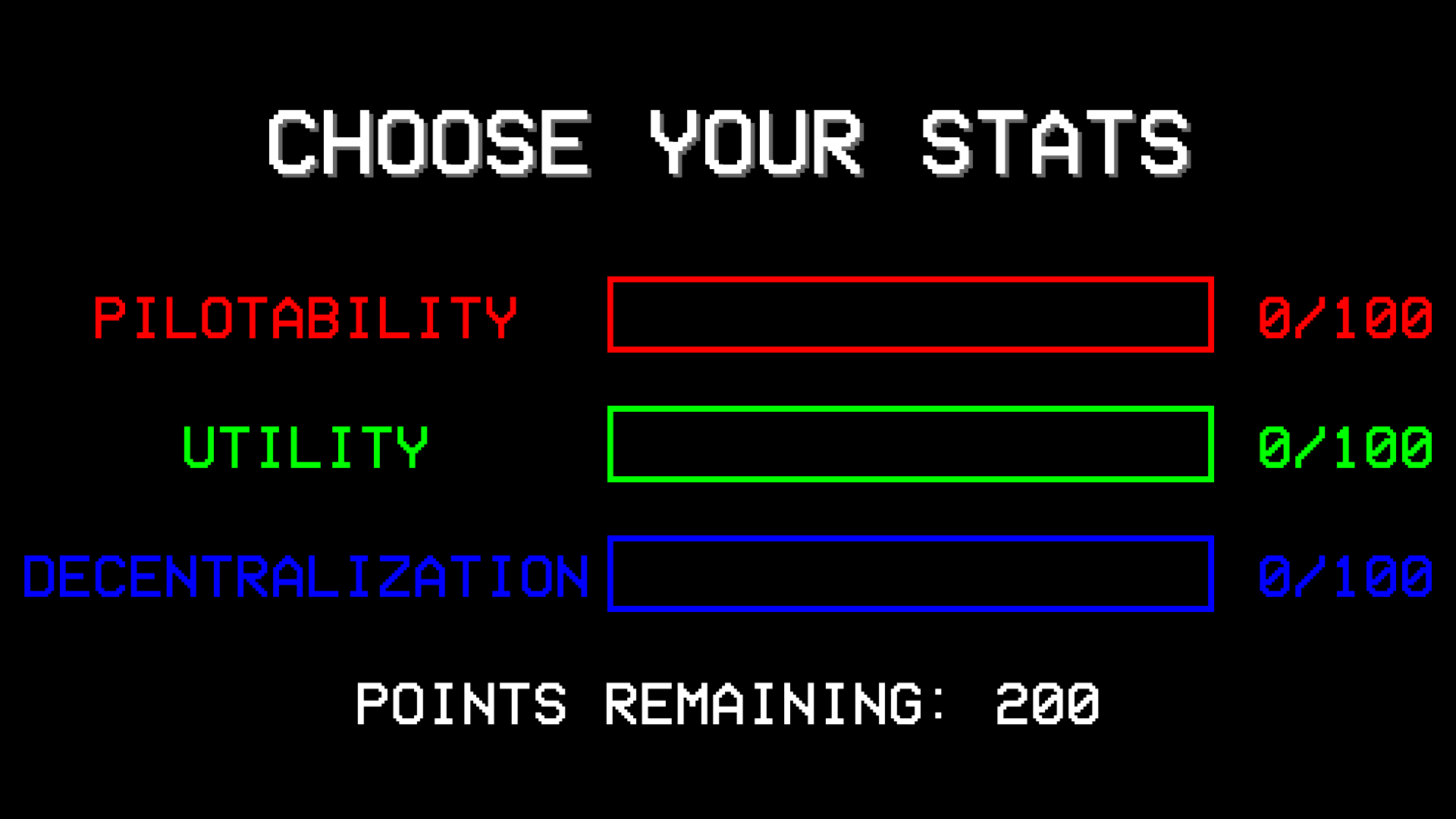

Of course, we do not need to sacrifice a feature entirely. This trilemma should be seen more as a distribution of stats, where each of the 3 features can have up to 100 points, but only a maximum of 200 points can be allocated.

However, before showing some examples, it is necessary to explain why decentralization, utility, and pilotability are chosen to show the trilemma.

How the trilemma works

Utility

In the blockchain industry, the vast majority of projects have their, cryptocurrency, known as a “token”.

The usefulness of this token varies from one protocol to another. It can be completely useless, just as it can be fundamental to the protocol with which it is associated:

- Tokens can have no utility at all, other than to raise funds from venture capitalists and use end-users as exit liquidity (we've seen it at DeFi Summer, and it will also happen at DeFi Renaissance)

- Tokens can have no governance utility, but financial utility like less fees on the protocol usage, or a percentage of the protocol revenue

- Tokens enabling holders control over a specific part of the protocol, where holders are invited to vote to provide external information to the protocol

- Tokens can be of general utility, where their holders can take control of the entire protocol if their voting power is large enough

The token utility is crucial for positioning our governance within this trilemma.

Pilotability VS Decentralization

If the token utility is significant, we must ask ourselves this question: Do we want governance capable of moving quickly and reacting rapidly to unforeseen events?

If yes, then the observation is as follows: the more important a token's utility is for governance, the more significant its intermediation becomes

We can distinguish 3 scenarios for governance tokens:

The token has no utility

Holders have no influence, and that's it. For there is no governance, the protocol must work all by itself, like Liquity V1 (we'll talk about it later)

The token has a specific utility.

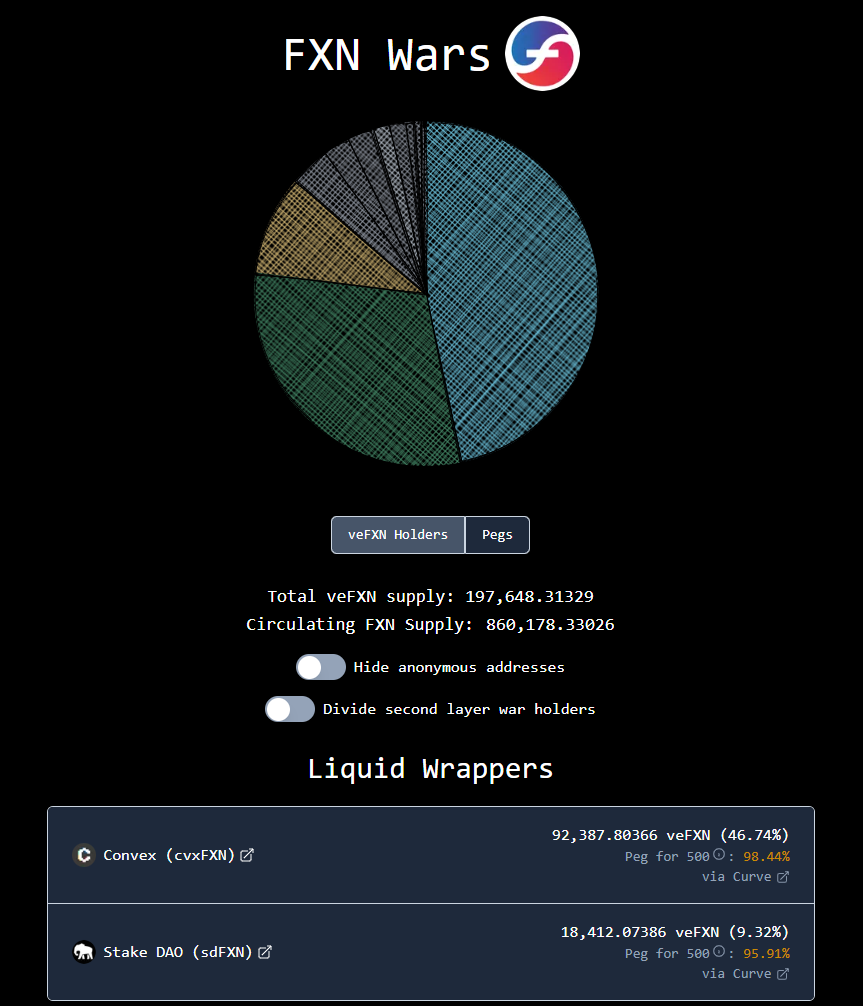

In this scenario, token holders are invited to vote to provide external information to the protocol. For example, we have the "weekly gauges" on Curve or Velo/Aerodrome where token holders must vote on specific liquidity pools to improve their yields.

Thus, the project can adapt its functioning thanks to the community serving as an oracle, like if the team were building a car and the community controlled the steering wheel.

For these tokens with a precise utility, some intermediaries allow us to vote on our behalf. These are "liquid wrappers" in which we exchange the voting power of our tokens for benefits related to our votes.

We have liquid staking for Ethereum, so liquid wrappers are "liquid staking" for ERC-20 tokens.

For example: the first liquid wrapper in existence is Convex which has been noticed for controlling more than half of the voting power across several projects, the first being Curve and the most recent being f(x) Protocol.

The token has a general utility.

For this type of governance, whoever owns the token owns the protocol. Sky (formerly MakerDAO) and Aave are the best examples of this category, as no single company is linked to these projects.

It is a set of providers who are completely independent of each other, but they coordinate through governance votes.

Token holders' participation is essential, but this role is demanding: it involves in-depth knowledge of the protocol and monitoring its activity. Not everyone has the time or energy to do so.,table, there is a recentralization through these delegates.

For example, when observing the votes executed on Sky's governance, 5 delegation platforms systematically concentrate the majority of voting power.

The brute-force solution is to increase the number of participants and ensure that there is no obvious leader (just like Bitcoin and Ethereum do), but the consequences are that governance takes much more time for everything.

The three "Pick Two"

If we choose 2 specifications at 100% and the third one at 0%, the answer would be something like this:

Autocracy (Sky)

Autocracy is the governance that chooses utility and manageability at the expense of decentralization.

In the context of this article, autocracy is defined as governance in which development decisions depend on token holders but where a single actor has a monopoly.

Remember the 5 delegation platforms that systematically appear in Sky's governance proposals? Well, it seems that the voting power of these 5 platforms comes from a single person, namely the founder Rune Christensen.

According to the conclusions of OAK Research, over 80% of the voting power on the protocol belongs to him (74,179 / 96,030 MKR in MakerDAO's governance contract) through these delegation platforms.

Having a monopoly over the governance allows one, to, make decisions more quickly than other protocols, and adapt in case of emergency.

However, governance finds itself without safeguards, and this can lead to questionable decisions, notably the implementation of the "Seal Engine" which introduces the possibility of minting USDS using MKR tokens as collateral.

Governance has long rejected the implementation of such a mechanism due to the potential risks it poses to governance and the protocol as a whole.

Anyone notice which vault type DOESN’T get rate hikes? It’s the one where Rune is borrowing $13.5m from Maker. Presumably that’s just an oversight bc it’s an new vault type (MKR collateral) https://t.co/Gu75SrYiHj

— PaperImperium (@ImperiumPaper) November 30, 2024

But since the monopoly wanted it, it must be done. Of course, it grants itself preferential treatment on the interest rates because whoever owns the token owns the protocol.

Anarchy (Bitcoin, Ethereum)

Anarchy is the governance that chooses decentralization and utility at the expense of pilotability.

Rather than relying on companies or intermediaries, the number of participants is increased and everyone is given a say. This is the approach of Bitcoin and Ethereum where it is not possible to designate a leader.

The consequence is that Ethereum and Bitcoin take much more time to achieve their objectives and to react in an emergency.

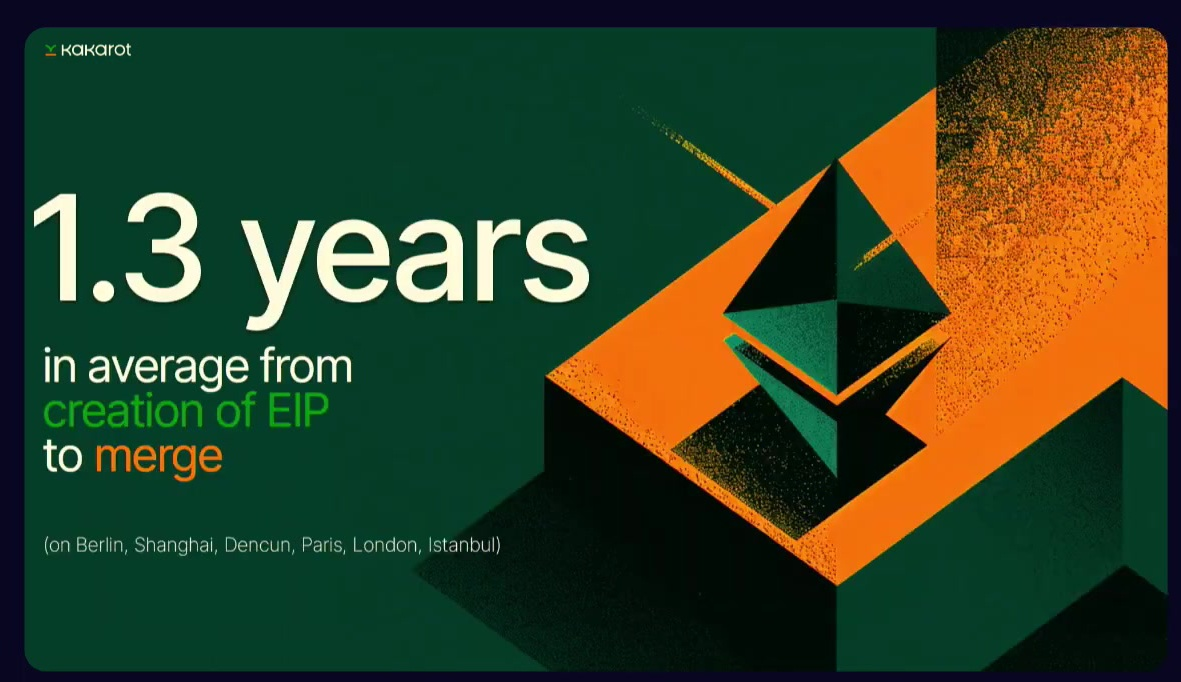

Example: An Ethereum Improvement Proposal (EIP) takes, on average, 1,3 years to go from technical specification to deployment due to all the governance layers it has to travel through.

Meanwhile, Kakarot (Ethereum Layer 2) core team scheduled and merged EIP-3074 in only two weeks.

(Yes, EIP-3074 was superseded by EIP-7702, but that was just to give an idea. By the way, we also that faster completion means Kakarot is much more centralized)

A more extreme example of onchain anarchy is Bitcoin. Unless you actively follow Bitcoin's development, it's very difficult to identify its Core developers, unlike some well-known Ethereum core developers.

But the counterpart is an even slower governance. Ethereum was already criticized for being slow in its evolution, but this is not much compared to Bitcoin, which has only had two major updates (SegWit in 2017 and Taproot in 2021) throughout its 16 years of existence.

Game Theory (Liquity V1)

Game theory is the governance that chooses pilotability and decentralization at the expense of utility.

Since governance can represent a threat to a project, some actors have designed projects without governance. For example, the stablecoin issuer Liquity V1 had no form of governance, and its functioning relied solely on game theory.

In reality, game theory is a double-edged sword:

- A protocol capable of fairly aligning the interests of all its participants regulates itself automatically regardless of the number of users and their will, so it's both controllable and decentralized.

- On the other hand, an unbalanced game leads to a protocol being less competitive than autocracies or anarchies.

Liquity V1 is a particularly enlightening example of the all-or-nothing nature of game theory:

- In an environment where borrowing rates for stablecoins were low (close to 0%/year), Liquity V1 was self-adapting effectively, even without governance.

- When average interest rates in DeFi exceeded 5%/year, this stablecoin issuer became even less competitive than others. The current collateral ratio is at 715%, which is not interesting for leverage.

The reason behind Liquity V1's shrinking market share

In Liquity V1:

- The user with the least collateral ratio is redeemed by other users to protect LUSD peg

- The redeemed users were losing money

- Minting LUSD implies a one-time fee from 0.5% to 5%

Decentralized finance has its average interest rates depending of the market sentiment (<4%/year is pessimistic, >10%/year is euphoric).

In 2023, DeFi rates got >5%/year meanwhile yield-bearing stablecoins were emerging. So users heavily sold their LUSD to get the yields, resulting in excessive selling pressure.

To protect the peg, there were lots of redemptions forcing the remaining users to drastically increase their collateral ratio, if they didn’t want to be redeemed, resulting il the current 715% collateral ratio to have a safe position in Liquity V1.

In other words, Liquity V1 works extremely well in low-interest-rate environments but no longer works outside of those conditions.

Nuanced approaches

What is interesting in decentralized finance, in general, is that we are seeing increasingly nuanced approaches. We are trying to find the right balance between Utility, pilotability, and decentralization to converge all actors' interests.

Velo/Aerodrome

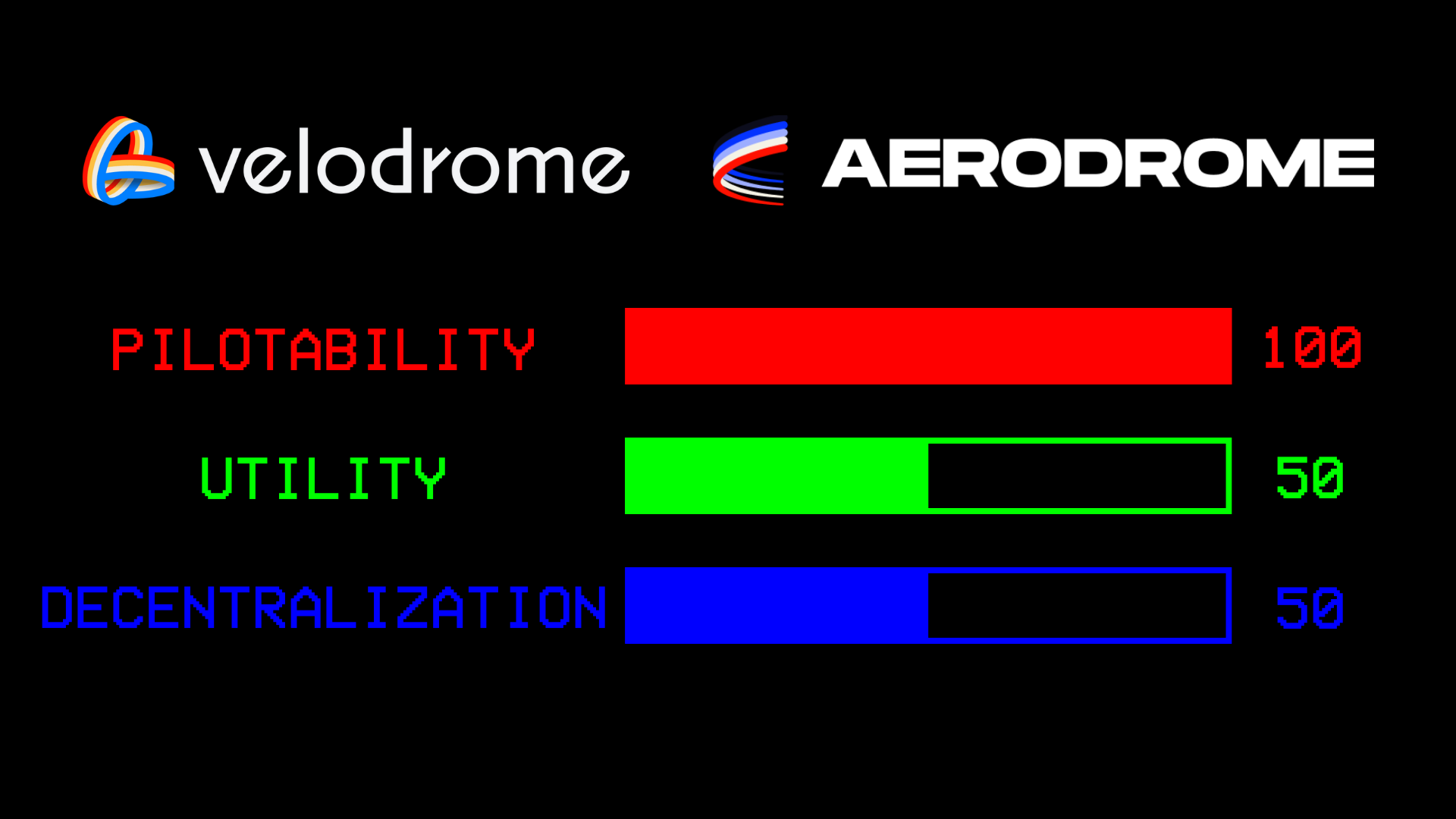

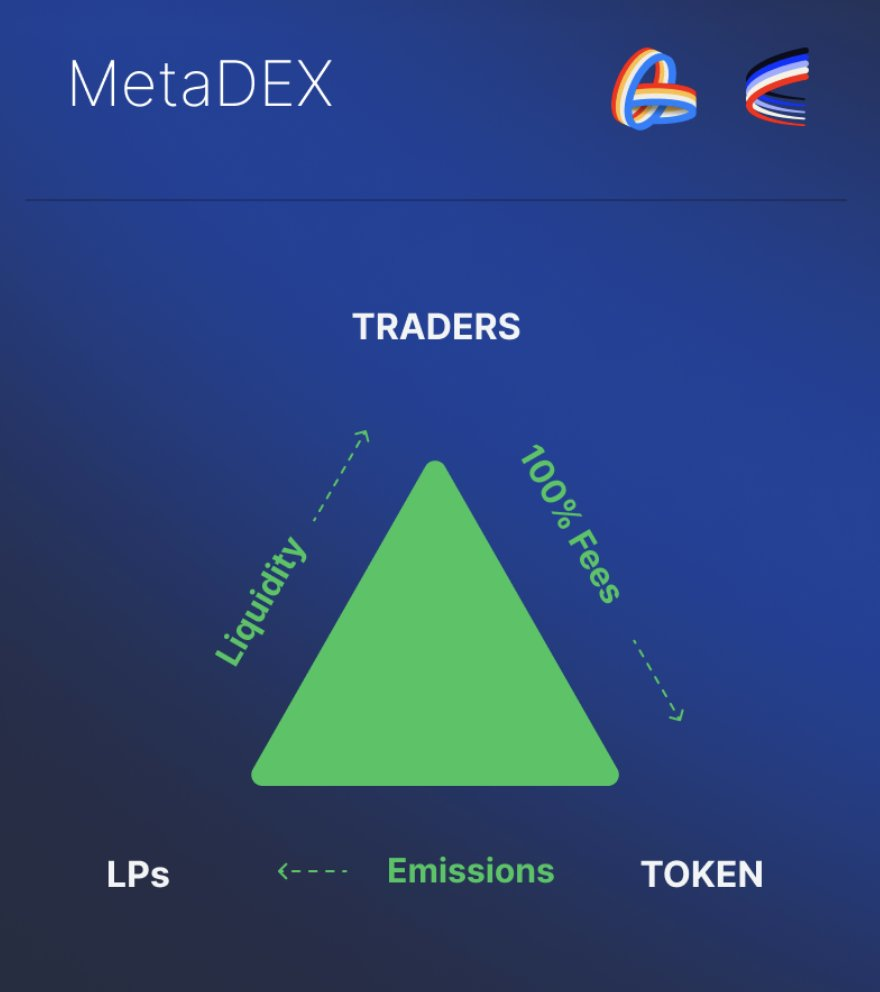

Velodrome and Aerodrome are the respective main AMMs of Optimism and Base where anyone can create any liquidity pool with a multiple choice of liquidity structures:

- x*y=k pools for volatile assets (Uniswap V2)

- Stableswap for stablecoins (Curve)

- Concentrated Liquidity ("CL") pools for blue chip assets (Uniswap V3)

Regarding this aspect of the protocol, the contracts are immutable and the VELO and AERO tokens have absolutely no influence.

However, these tokens influence the revenues perceived by token holders and liquidity providers (LPs):

- Each week, token holders must vote on liquidity pools most likely to collect the most swap fees

- The more a liquidity pool has voting power, the more emissions of new VELO and AERO tokens are significant on this pool (these emissions are the LP's revenues)

- 100% of fees collected by a liquidity pool are redistributed to their voters (token holders who don't vote get nothing)

- At the end of the week, repeat

To summarize, we have a token that specifically intervenes on incentives, and which financially incentivizes voters and LPs to direct liquidity toward pools generating the best economic activity.

In other words, the utility of VELO and AERO does not allow controlling everything, but its financial incentives enable protocols to react quickly.

Liquity V2

The main difference in Liquity V2 is that stablecoin issuance requires an annual interest rate (chosen by users) and it is the users paying the lowest interest rates who get redeemed first.

- 75% of the interest paid by users goes into the stability pool

- The remaining 25% are directed to any address. This can be a liquidity pool or other entities possessing an onchain address.

The utility of LQTY is relatively minimal:

- No influence on the project's functioning itself, whether in stablecoin issuance, interest rates, or the Stability Pool

- Even in the event of a governance attack, only 25% of revenues paid by users would be disrupted

Finally, as with Liquity V1, the goal of V2 is to offer a system primarily based on game theory. But this protocol initiative mechanism allows a minimum margin of maneuver to evolve and stay competitive in a landscape where yield-bearing assets are the new meta.

Possum Labs

Until now, we have addressed governance solely through the prism of ERC-20 tokens. So, what prevents us from creating governance with other types of tokens, such as NFTs?

This is precisely the approach of Possum Labs, which plans to implement NFTs in its governance with a future update named Core V2.

Portals

Possum Portals is a future yield protocol where you can stake tokens or stablecoins to get yields in advance.

Future yield protocols such as Pendle or Spectra use an AMM (Automated Market Maker) to make future yields tangible.

Meanwhile, Portals adopts a timelock logic: the longer we lock the tokens, the more we get immediate yields (Example with 10% APR: $1000 lock for 1 year = get $100 now)

Depending on the portals, yields are generated by Vaultka (a yield-generating protocol) or users harnessing arbitrage opportunities when the value of accrued assets exceeds the fixed PSM required to buy them.

Just like Velo/Aerodrome and Liquity V2, this part of the protocol cannot be influenced by governance.

Possum Core

The PSM token is the hub of the whole Possum ecosystem. It is used for arbitrage opportunities, reducing the locking time, and Possum Core which we can consider as a "payment stream" in PSM tokens.

In Core V1 (current version) PSM stakers can control a whitelist of addresses eligible for this payment stream. Those addresses can be:

- Existing portals to boost the future yield

- Liquidity pools (e.g. PSM/ETH) to bring more rewards for LPs so they're incentivized to bring more liquidity

- Compensation for initiatives (fun fact: the founder 0xPossum donated his PSM share to the Possum Core contract, and gets compensated directly by Possum Core)

The thing is, power over the whitelist and payment streams both rely on PSM tokens. There needs to be a separation, and this is where Core V2 comes in.

Possum Labs launched a collection of 325 Passel NFTs, which will have utilities in Core V2:

- NFT holders will control the whitelist of Possum Core

- Each NFT has its voting power according to criteria like protocol usage, voting history, and PSM staking to decide which address is eligible for PSM streams or not

To sum it up, Possum Core is useful to bring incentives, but the central system cannot be modified by the token.

These are just a few examples, and there are certainly others, but it's clear that DeFi as a whole is taking onchain governance seriously, and that research is being carried out into the most suitable trade-offs for converging the respective interests of users for a given financial service.

Limitations

To write this article, some hypotheses had to be made that limit the application of this on-chain governance trilemma.

This article does not consider potential governance bypasses to make decisions with immediate effects on the protocols concerned, which renders on-chain governance inoperative.

In 2023, when the Curve founder was trying to make OTC sales of his CRV token to prevent liquidation on his loan, several protocols directly bought CRV without consulting their governance upstream. Aave was the only protocol that respected its process in due form.

This article does not consider the influence that entities other than delegation platforms can have.

Protocols such as Uniswap or Morpho cannot serve as examples in this article for two reasons:

- Their respective companies (Uniswap Labs and Morpho Labs) are responsible for development

- Governance is controlled by venture capital funds

This situation can evolve in the coming years, but onchain entities like delegation platforms don't have enough influence to make onchain governance relevant.

This article is for educational purposes only. The main purpose was to provide an overview of onchain governance, the different trade-offs it faces, and highlight approaches to deal with these trade-offs. It goes without saying that onchain governance presents subtleties that require deeper exploration beyond this article.